Neurotechnologies through the lens of human rights law

Neurotechnologies through the lens of human rights law

Authored by: Ben Howkins and Julie Vinders

Reviewed by: Corinna Pannofino and Anaïs Resseguier

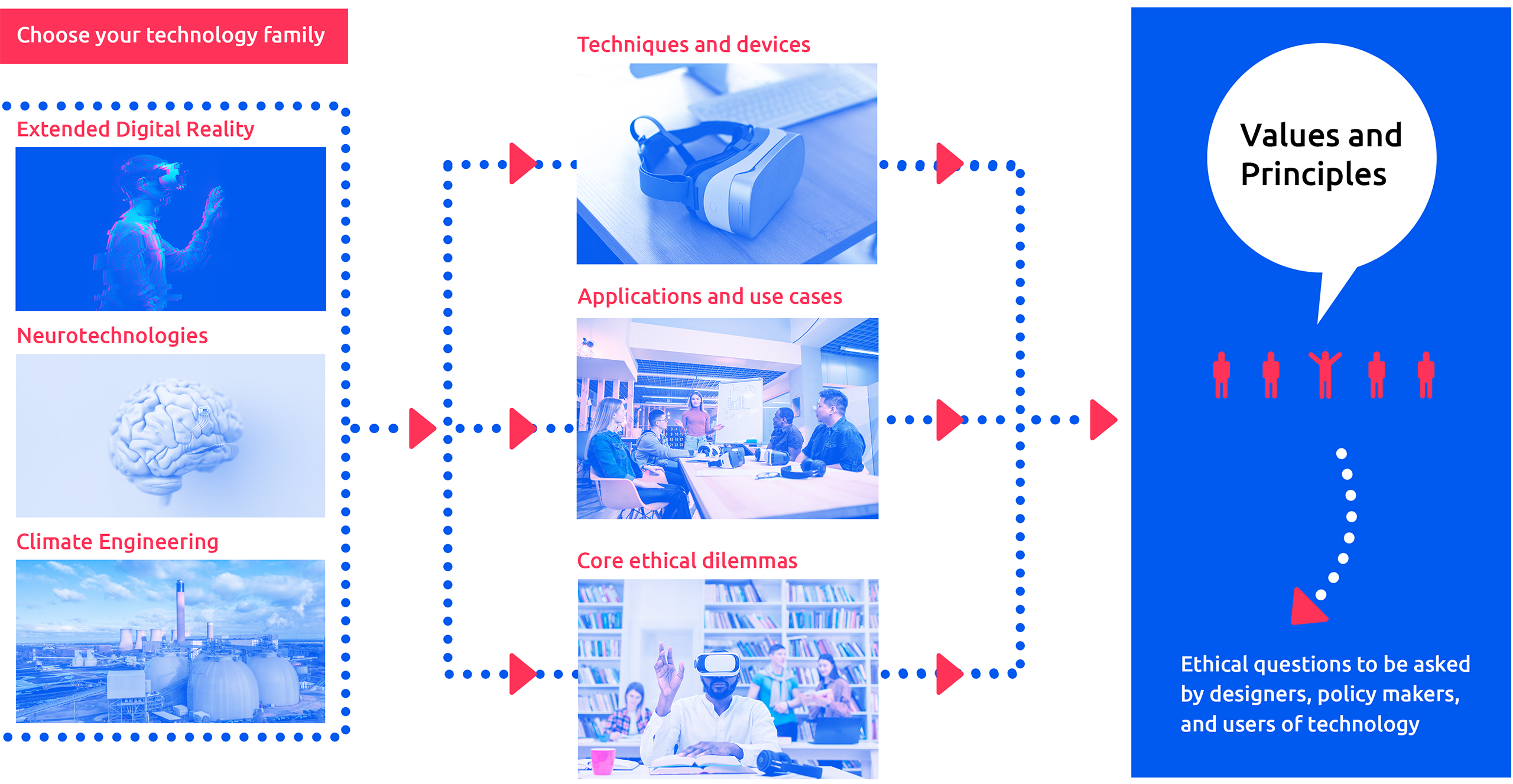

Technological innovation can both enhance and disrupt society in various ways. It often raises complex legal questions regarding the suitability of existing laws to maximise the benefits to society, whilst also mitigating potentially harmful consequences. Some emerging technologies even challenge us to rethink the ways in which our fundamental rights as human beings are protected by law. What happens, for example, to the right to not self-incriminate if advanced neurotechnologies in the courtroom can provide insights into a defendant’s mental state?

As a means of directly accessing, analysing, and manipulating the neural system, neurotechnologies have a range of use applications, presenting the potential for both enhancements to and interferences with protected human rights. In an educational context, insights on how the brain works during the learning process gained from research on neuroscience and the use of neurotechnologies may lead to more effective teaching methods and improved outcomes linked to the right to education. This may enhance the rights of children, particularly those with disabilities, yet more research is required to assess whether there is the potential for long-term impacts to brain development. The (mis)use of neurotechnologies in the workplace context, meanwhile, may negatively impact an individual’s right to enjoy the right to rest and leisure by increasing workload, or instead positively enhance this right by improving efficiency and creating more time and varied opportunities for rest and leisure.

Neurotechnologies and medical treatment

The primary use application of neurotechnologies is in a clinical context, both as a means of improving understanding of patients’ health and as a means of administering clinical treatment, the effects of which have the potential to enhance various protected human rights in conjunction with the right to health. For example, neurotechnologies may facilitate communication in persons whose verbal communication skills are impaired, the benefits of which are directly linked to the right to freedom of expression. Additionally, neurotechnologies may be used to diagnose and treat the symptoms of movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, thereby potentially enhancing the rights to dignity and autonomy of persons with disabilities.

However, the clinical use of neurotechnologies requires compliance with legal and bioethical principles such as consent and the right to refuse treatment, without which the protected rights of users may be interfered with. A particular concern is that the clinical use of neurotechnologies may lead to infringements with the right to non-discrimination, specifically in the form of neurodiscrimination, whereby the insights from brain data processed by neurotechnologies form the basis of differential treatment between individuals, for instance in insurance and employment contexts. From this a key consideration emerges, namely whether brain data is adequately protected by the existing right to privacy, or whether there is a need for a putative right to mental privacy, amongst a range of novel human rights protections, including a right to cognitive liberty, a right to mental integrity and a right to psychological continuity. The essential premise behind these proposed ‘neurorights’ is that the existing human rights framework needs revising to ensure individuals are adequately protected against certain neuro-specific interferences, including the proposed ‘neurocrime’ of brain-hacking.

Neurotechnologies and the legal system

Neurotechnologies are also increasingly being used in the justice system, wherein they may enhance an individual’s right to a fair trial, for instance by ‘establishing competency of individuals to stand trial’ and informing rules on the appropriate ‘age of criminal responsibility’. However, the use of neurotechnologies may also interfere with access to justice and the right to a fair trial. For example, advanced neurotechnologies capable of gathering data on mental states consistent with one’s thoughts and emotions risks interfering with the right to presumption of innocence or the privilege against self-incrimination. An additional consideration in this context is the right of individuals to choose to or opt against benefitting from scientific progress, the relevance of which is that individuals cannot be compelled by States to use neurotechnologies, except in certain limited circumstances determined by the law. The enforced use of neurotechnologies in justice systems could therefore interfere with the right to choose to opt against “benefitting” from scientific progress, as well as the right to a fair trial and access to justice.

Neurotechnologies and future human rights challenges

Finally, whilst this study has highlighted the ways in which neurotechnologies may already affect the enjoyment of fundamental human rights, the potential for enhancements to and interferences with these protected rights may increase as the technological state of the art progresses. For example, although primarily contemplated within the realm of science fiction, in a future reality the use of neurotechnologies may challenge the strictness of the dichotomy between ‘life’ and ‘death’ by enabling ‘neurological functioning’ to be sustained independently of other bodily functions. This may affect States’ obligations to ensure the full enjoyment of the right to life, while also raising questions around the appropriate regulation of commercial actors seeking to trade on the promise of supposed immortality

Next in TechEthos – is there a need to expand human rights law?

The study highlights the importance of bringing a human rights law perspective into the development of neurotechnologies. The human rights impact assessment is a mechanism designed to help ensure that new and emerging technologies, including neurotechnologies, develop in a manner that respects human rights, while also enabling the identification of potential gaps and legal uncertainties early on in the development stage. The analysis also raises the question as to whether further legislation may be required to address these gaps. Crucial to this question is the need to strike a balance between ensuring technological development does not interfere with fundamental human rights protections and avoiding overregulating emerging technologies at an early stage and thereby stifling further development.

Read more about the human rights law implications of climate engineering and digital extended reality.

Share: